By Soni Sangha

US News & World Report

BROOKLYN, N.Y. — Broadies Key-Byas’ health troubles led her into foreclosure. In 2005, she sought treatment for what she would later learn was multiple sclerosis; she missed a few home equity loan payments in the process. In 2008, her bank told her she needed to repay her loan in full to avoid losing her childhood home. Desperate for a solution, she says she unwittingly signed away her deed to a company that promised to guide her, but instead tried to push her family out of their home.

“I didn’t know how foreclosure works,” she says. “All I know is I go to court and the judge says, ‘You’re out.’ It’s terrifying when there’s no one there to help you.”

New York state ultimately saved her. She benefitted from a broad-reaching foreclosure assistance program created from the payout of a lawsuit.

But the money is running out in states such as New York, Tennessee and Illinois, and advocates across the country worry about the longevity of their programs.

New York’s funds were set to expire March 31, but after a nail-biting state budget negotiation, legislators secured $20 million for the program to continue next year.

“What you’re seeing today is a strong commitment to fully fund these programs,” says state Sen. Brian Kavanagh, who chairs the housing, construction and development committee. “We have to work to make sure funding continues.”

In 2012, 49 states sued banks that issued predatory loans. (Oklahoma opted not to join the lawsuit.) They reached a $25 billion settlement, most of which was issued by the defendants as credits and services to homeowners; $2.5 billion went straight to the states, who used the money in different ways.

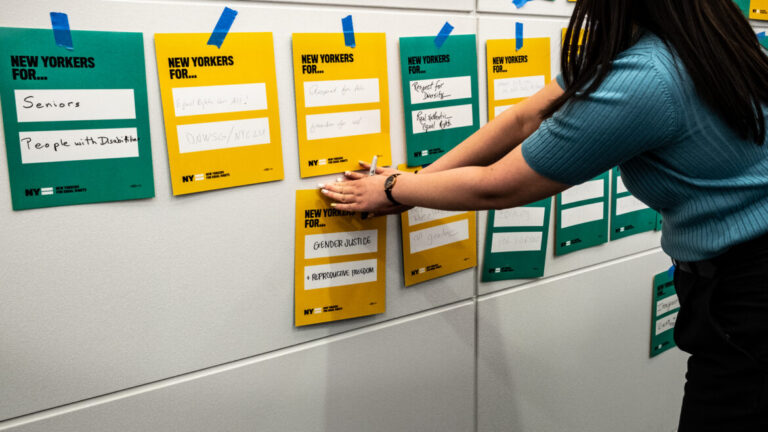

New York created a mandatory housing mediation program and a network of free legal services for homeowners facing foreclosure – including Key-Byas, who wasn’t a victim of the type of bank malpractice that spurred the national lawsuit. Advocates had been desperately lobbying state senators to continue funding the program after Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s version of the budget omitted it.

In Illinois, where the foreclosure rate is among the 10 highest in the country, legislators were inspired by the Empire State’s actions but they didn’t want to increase their state’s budget. Instead, they tried to create self-sustaining programs. Counties are now funding their own mediation programs. Much of Illinois’ money seeded community revitalization programs, such as land banks, which give governments or nonprofits a low-cost way to acquire and rehabilitate abandoned or foreclosed property. Illinois officials hope state money helps those programs establish a track record to secure new financing.

“We went into this knowing the source of funding was static and would not continue. Great effort was made to fund projects that both could leverage other resources and grow capacity so they could continue on when funding done,” says Susan Ellis, Chicago bureau chief of the Consumer Fraud Bureau for Illinois’ attorney general.

California was one of several states that diverted their settlement funds to fill budget gaps; housing advocates sued. While about $10 million went to housing nonprofits, the state spent $331 million on housing programs created before the foreclosure settlement. Advocates filed a lawsuit claiming the state violated its spending mandate. In 2018, the appeals court agreed. The state is now challenging that ruling.

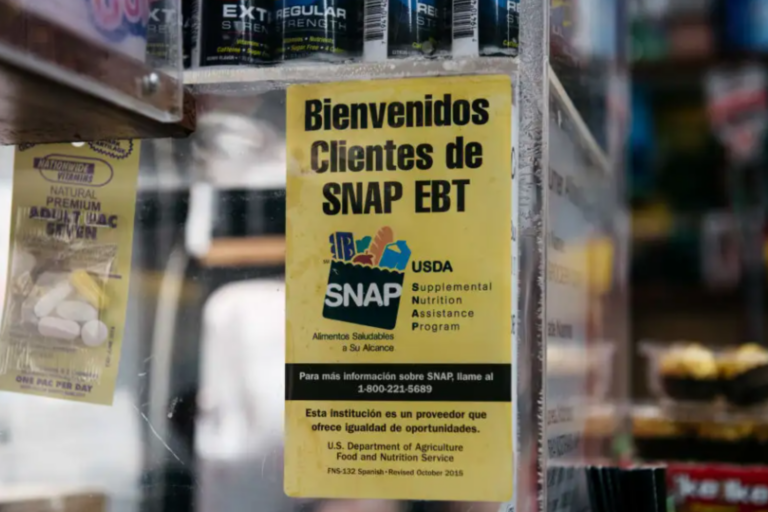

“The problem is state legislators don’t know what the funds are for to begin with,” says Julian dela Cruz, attorney for the National Asian American Coalition. “So once it reaches their account they feel like it’s fair game to use for whatever purpose they want.”

“We’re all staring down the abyss wondering what’s going to happen, is all this going to collapse once funding is gone or are we going to keep really great infrastructure in place,” says Caroline Nagy, deputy director for policy and research at the Center for NYC Neighborhoods, part of the state’s coalition of foreclosure assistance providers. “We got past one foreclosure crisis and put in protections and services but what happens if they’re not there anymore? Could we wind up right back where we started in another foreclosure crisis?”

Before 2007, foreclosures were considered rare. Then, the mortgage crisis hit. From 2008 to 2012, 5 million homes either had been foreclosed or received a filing. In 2009, one out of every 45 homes received a filing. Things have improved; national rates are at pre-crisis levels.

But not in New York. In 2017, the state had its highest foreclosure rates since 2006. Ever since the crisis, state officials wanted to strengthen homeowner protections. They used their portion of the funds to expand legal services and create a mandatory settlement process, in which the bank and the homeowners try to reach an agreement before a foreclosure can be acted upon. In the last few years, there was a spike in senior foreclosures due to reverse mortgages, Nagy says. So the network that was created was able to push for services to cover those homeowners.

“New York has been the gold standard when comes to foreclosure events both in terms of passing laws, as well as dedicating funds for expansive foreclosure prevention,” says Rose Marie Cantanno, associate director of foreclosure prevention with the New York Legal Assistance Group.

Key-Byas is an example of that homeowner support. In 2000, she took out a $30,000 home equity loan to build credit. She missed three payments and, in the thick of the housing crisis, the bank filed for foreclosure.

When Key-Byas’ case went into mediation a few years later, the program was just getting off the ground. Today, a letter notifying you of an impending foreclosure would include a list of legal aid organizations. But when Key-Byas was scrambling for help, she recalls meeting with attorneys she couldn’t afford. In 2014, Homeowners Assistance Services called her. The private company promised help and she believed them.

In a well-staffed office in Queens, New York, she met a man who said he would represent her. She says they gave her a check for $50,000, which she thought was a loan to repay the bank. She signed papers that she says didn’t disclose she was signing over the deed to her house.

“My ‘Spidey senses’ were going off. They wouldn’t answer me when I asked, ‘How do I pay you back?’” she recalls to U.S. News, in an interview along with her attorney.

She says Homeowners Assistance Services aggressively tried to force her and her family out of their home. She contemplated moving, and she considered suicide. Instead, she found New York Legal Assistance Group, one of the organizations in the state network. The settlement funding allowed it to take on complicated cases such as Key-Byas,’ which it didn’t do before. Ultimately, three people behind Homeowners Assistance Services were arrested, and district attorneys called for stricter prosecution of deed fraud as a result.

“Scammers prey on seniors and have a real impact on communities of color,” says Noelle Eberts, Byas’ attorney at NYLAG. “Before (our network) was there, there wasn’t anybody to say, ‘This is what’s happening and this is wrong.’”

Meanwhile, Key-Byas, who is still in her home but still in litigation over her deed, counts the New York state program as a blessing.

“Even though they stopped this type of theft, there will always be a crook, always someone to find a new way of stealing something from somebody,” she said. “And it won’t stop – unless the money is there to help you get a good lawyer.”

Origionally published in U.S. News & World Report on April 4, 2019.