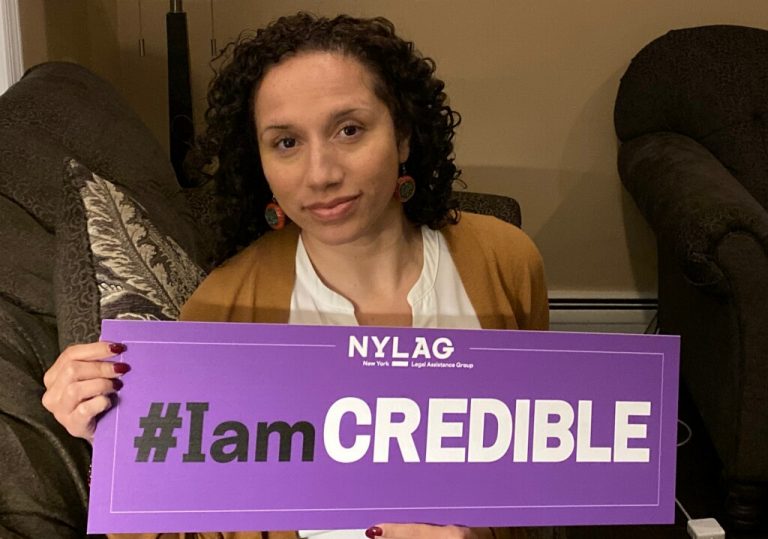

It’s not uncommon for our systems to question whether a survivor of domestic violence or sexual assault is credible just because a witness doesn’t behave, or look, the way the court expects. As part of NYLAG’s #IamCredible campaign, we’re reframing how we think about the credibility of a survivor’s story.

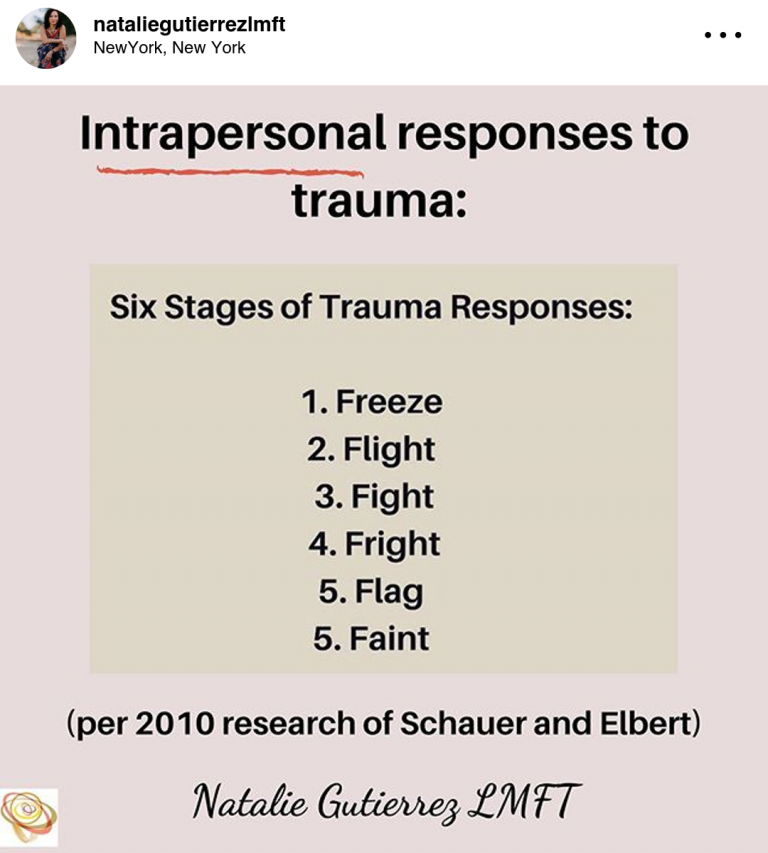

We spoke with trauma therapist Natalie Y. Gutierrez, LMFT, to better understand how trauma impacts a survivor, including how they retell their experiences. Gutierrez has worked with survivors for nearly 10 years, specializing in intergenerational trauma as well as how societal systems perpetuate violence, revictimizing survivors. You may have seen her on Instagram as she has a popular account about trauma with more than 10k followers.

What is trauma? How does it change the brain or the way someone navigates the world?

Gutierrez: Trauma can be a single incident traumatic event or prolonged exposure to a series of ongoing toxic stress. This marks the difference between PTSD and Complex PTSD. PTSD has sensory triggers that stem from these single incident traumas. CPTSD have both sensory and emotional triggers that originate from more ongoing trauma, like abuse from caregivers.

Trauma is when a person encounters a situation where they are immobilized and helpless, unable to remove themselves from a threat and therefore the body goes into a fight/flight or a dissociative state. The body and brain (amygdala) store this information and anytime we encounter similar sensory stimuli or emotional triggers, our autonomic nervous system activates and prepares us for survival.

What are some of the common responses to a traumatic event? What are some unexpected reactions?

G: Common responses to trauma include hypervigilance, being constantly guarded in a fight/flight response, feeling withdrawn or numb, feeling foggy, having flashbacks and being triggered. When it comes to trauma, it’s safe to say that no two experiences are the same and everyone grieves and deals with trauma in their own way.

How does surviving a traumatic event affect one’s retelling of it?

G: It depends on the person. Since no two people are the same, some people can re-tell a traumatic event and remember every single sensory detail of the incident. Some people may not remember anything at all due to dissociation. Our bodies and brains do what they need to do to help us survive traumatic events in the way that feels safest for us.

For those listening to a survivor who may share their story publicly (i.e. as part of the court cases), what should they remember/consider?

G: Anyone listening to such vulnerable testimonies and stories of survivors should approach them with gentleness and compassion. Avoid victim-blaming and looking for faults or what the victim did “wrong”. No person deserves to be victimized under any circumstances. Listen with an open heart, nonjudgmentally, and ask how they can be supported in a way that feels right for them.

For a survivor who may need to/chooses to share their story publicly, what advice do you have for them?

G: Sharing your story is a profound thing. Remember that to share your story is to liberate yourself from its power over you and to reclaim your life. It’s also important to remember that you may naturally receive some unhelpful, hurtful criticism from hurt people afraid of doing the work you’re doing. This isn’t a reflection of you and is only a sign of unresolved trauma in the critic.

The majority of our clients are experiencing poverty, and many are people of color, immigrants, and LGBTQ people. How can these identities interact with one’s experience with trauma or seeking help?

G: There are definitely inequities in both the amount of trauma experienced within marginalized communities and how this trauma is viewed in the eyes of people in dominant culture. People identifying themselves within various intersections of LGBTQ+, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), people with disabilities, are subject to increased systemic oppression, hate crimes, race-based trauma, mass incarceration, poverty, displacement due to gentrification in their communities—and if we look at what is happening in our southern border—separation of families and migrant children.

These experiences are unique to people in marginalized communities and impede their hopefulness in seeking help, create distrust of authority, perpetuate internalized racism, internalized homophobia, and more. Furthermore, folks living in poverty are unable to find accessible mental health services.

To learn more about Natalie Y. Gutierrez, visit traumacounselingnyc.com

To get involved with #IamCredible, visit nylag.org/IamCredible