The state legislature has passed a measure intended to counter a court ruling that made it easier for lenders to win cases against homeowners. Sponsors say industry warnings about unintended consequences are overblown.

By Sam Mellins

New York Focus

Some homeowners facing foreclosure stand to get relief under a bill passed by the state legislature and now heading to Gov. Kathy Hochul’s desk for either a signature or veto — and she’s not saying which.

The measure takes aim at a Feb. 2021 decision from the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in New York State, that reopened hundreds of foreclosure cases that homeowners thought they had won because lenders missed a key deadline.

In the case, known as Freedom Mortgage Corporation v. Engel, the Court of Appeals ruled that lenders could proceed with foreclosures nonetheless — and even revive dormant cases.

The bill that passed the state Senate Tuesday by a 52-10 vote following approval in the Assembly would overrule that decision, as well as another related to foreclosures from a lower-level state court.

Hochul’s staff has met with representatives of the mortgage industry to hear their reasoning for opposing the bill, New York Focus and THE CITY have learned.

A spokesperson for Hochul did not immediately respond to a question on whether she has met with supporters.

Real estate and banking industry players have been lobbying against the bill since last year, including J.P. Morgan Chase, Capital One and KeyBanc.

The Engel decision stands to save mortgage lenders billions of dollars, and place potentially thousands of homeowners statewide under threat of foreclosure. Some of those homeowners had already won their cases when Engel was decided — but the decision allowed lenders to revive their cases or appeal to higher courts.

Following the ruling, lenders moved to reopen hundreds of cases statewide that had previously been resolved in favor of homeowners — and are continuing to do so, foreclosure defense attorneys told New York Focus.

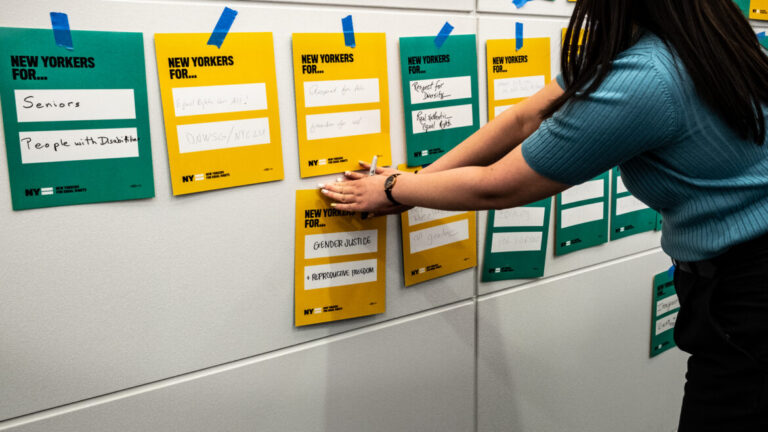

“We’ve been in damage control mode since Engel came down,” said Julie Howe, an attorney at the New York Legal Assistance Group’s Foreclosure Prevention Project. “A number of people, including several clients of mine, who thought that they could have their houses without worrying about the threat of foreclosure — now they’re back into worrying that they’re going to lose their homes.”

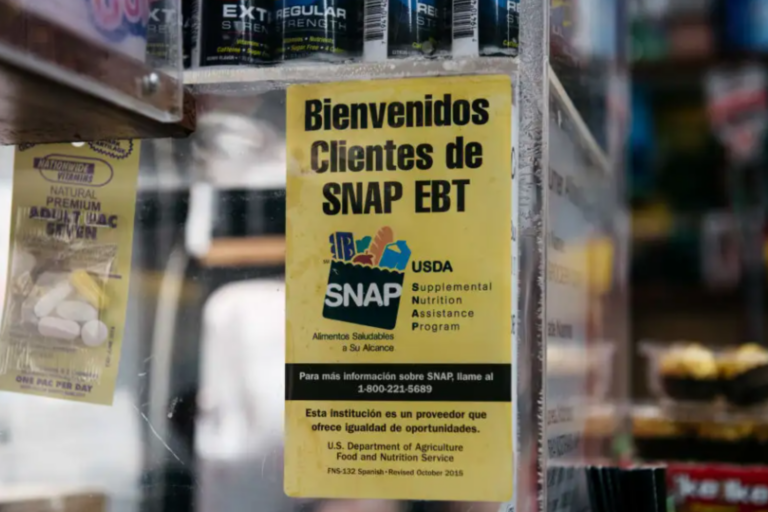

Jacob Inwald, director of foreclosure prevention at Legal Services NYC, told New York Focus that “almost all” of the cases reopened after the Engel decision date back to the 2008 financial crisis.

“There were an enormous number of cases known as the ‘shadow docket’ where the plaintiffs started the cases but they never filed the paperwork that they were required to,” Inwald said, meaning that the cases eventually expired — until the decision in Engel revived them.

‘Multiple Bites of the Foreclosure Apple’

The decision in Engel overturned lower courts’ readings of New York law that had stated that if lenders don’t start legal proceedings within six years of first moving to foreclose, or notify borrowers if they decide to stop seeking foreclosure, the foreclosure suit becomes invalid.

Six years is generally enough time to get a suit underway, or notify borrowers that the lender has decided not to pursue foreclosure, but individual mortgages packaged in massive portfolios for investors can slip through the cracks, so lenders do sometimes let that time period expire or neglect to notify borrowers.

“It’s more common than we’d like it to be,” acknowledged Adam Swanson, a partner at the law firm McCarter & English who represents lenders in mortgage disputes.

Before the decision, the six-year limit kept running until a lender informed a borrower that it had decided to stop seeking foreclosure.

But in its decision in the Engel case, the Court of Appeals found that when a lender ends a suit, even if they never notify the borrower, it stops the clock automatically, and allows the lender to sue for foreclosure again on the same loan, even if more than six years have elapsed.

“If Engel is permitted to stand, lenders will get multiple bites of the foreclosure apple,” Assemblymember Helene Weinstein (D-Brooklyn), the lead Assembly sponsor of the bill to overrule Engel, said in a statement to New York Focus. “We need to return to the law which existed prior to Engel, which provided a clear six-year statute of limitations.”

After the Court of Appeals decided the Engel case in February 2021, legislators moved quickly to attempt to overturn it. A bill to reverse many of its effects was introduced in the state Senate in March 2021, and a separate bill introduced in the Assembly in May 2021. The two bills were reconciled into one version in 2022.

‘Sky is Falling’ Arguments

The bill would restore the status quo from before the Engel decision, and in certain ways would actually go further in expanding homeowners’ legal protections.

Representatives of New York’s mortgage lending industry claim that its sponsors and supporters don’t understand that the bill could actually end up making it harder for homeowners to work with lenders to avoid foreclosure, by making it too risky for lenders. Foreclosure defense lawyers, on the other hand, charge that lenders are exaggerating the bill’s effects out of concern for their bottom lines.

Currently, lenders have the ability to reset the six-year clock by unilaterally deciding to stop seeking foreclosure, and then starting a new lawsuit — a tool they had even before the Engel decision. The bill says that if lenders withdraw their lawsuit seeking foreclosure, that would no longer reset the clock. New York law generally bars plaintiffs who voluntarily discontinue a lawsuit from suing again based on the same claim.

Instead, to reset the clock, lenders could reach an agreement with borrowers to adjust the terms of the mortgage to prevent foreclosure — a maneuver known as a “loan modification.” In exchange for their consent to stop the clock, borrowers could request changes such as a lower interest rate, or a longer timeframe for repayment with smaller monthly installments.

But representatives of the mortgage industry say the proposed fix is not so simple. They told New York Focus and THE CITY that they believe the bill would prevent lenders from foreclosing on mortgages that have been modified — with the result that if a homeowner defaults after a modification, lenders will lose their capital.

According to their reading of the bill, if a borrower defaults more than six years after the lender first sought foreclosure, the time limit would bar the lender from foreclosing on the modified loan.

“I think lenders are going to be more hesitant to provide loan modifications, knowing if there’s a subsequent default, they may not be able to recover” their investment, said Natalie Grigg, a partner at Woods Oviatt Glattman, who represents lenders and investors in foreclosure lawsuits.

Weinstein said that this is a “misunderstanding” of the bill.

If a homeowner defaults on a modified mortgage, that “would give rise to a new cause of action under the modified agreement,” allowing another foreclosure suit, the Assembly member said in a statement. “The original default date would not be relevant whatsoever,” she added.

Mortgage industry representatives also say that these additional steps its lawyers would have to take to stop foreclosure suits will make lenders less likely to negotiate settlements, and encourage them to press for foreclosure instead.

“It’s going to make what’s called ‘loss mitigation,’ or working out loan modifications, so difficult for the industry to implement that they’re not going to have any incentive to agree,” Swanson said.

This industry argument “might be right,” said Howe, the foreclosure defense lawyer. But she points to lenders’ obligation under New York law to negotiate with borrowers in good faith to reach settlements that will prevent foreclosures — and hopes that preventing lenders from effectively restarting their suits will encourage them to reach deals.

Lenders’ representatives also warn that additional legal responsibilities in the foreclosure process will lead to higher legal costs, which would then be passed on to homeowners in the form of higher interest rates on mortgages.

“Lenders could pull out, or potentially interest rates would be higher in New York because they’d have to factor in” additional legal costs, Swanson said.

In her statement, Weinstein said that the bill’s opponents were exaggerating its effect.

“While some in the banking industry have opposed the bill by raising “sky is falling” arguments concerning future mortgage lending in New York, this bill basically takes us to where the law stood the day before the Engel decision came down, which certainly worked for the mortgage lending industry in New York for many, many years,” she said.

Monday Meeting

On Monday, representatives of the mortgage industry met with Hochul’s staff to make their case against the law, Grigg and Swanson told New York Focus.

“We just were able to get a call put together with some of the assistant counsels with the governor’s office who found it very informative,” Grigg said on Monday. Hochul’s staff did not indicate whether Hochul plans to sign or veto the bill, but Grigg said she felt the meeting was “very important for them.”

A spokesperson for Hochul did not address questions from New York Focus and THE CITY about the governor’s position on the bill, or the topics discussed at the Monday meeting with mortgage industry representatives.

Originally published in New York Focus and THE CITY on May 3, 2022