Beth Fertig

Gothamist

Unlike most children his age, 21-month-old Jaciel has never nursed from a bottle or his mother, and he’s never eaten Cheerios. All of his nutrition comes through a feeding tube.

Five times a day, his mother Laura hooks the thin tube to a little port in his stomach that resembles a pacifier. It’s connected to a sack of fortified milk and an electronic device about the size of a tablet that monitors the flow. She then straps him into a special high chair so he can’t dislodge the equipment. He sits up straight, cheerfully looking around the living room of their small but tidy apartment in Westchester.

Jaciel needs the tube because – like many other kids with Down Syndrome – he was born with a congenital heart defect that makes it difficult for him to eat normally. He also had a cleft palate. Laura says he’s already had five operations for the palate and other medical issues, and is now waiting for open heart surgery that will allow him to eat instead of using the tube.

“If everything goes well and the treatment works, I’m going to be 85 percent independent from him,” she said in Spanish. “All I want is for him to be independent and happy.”

Listen to reporter Beth Fertig’s story on WNYC:

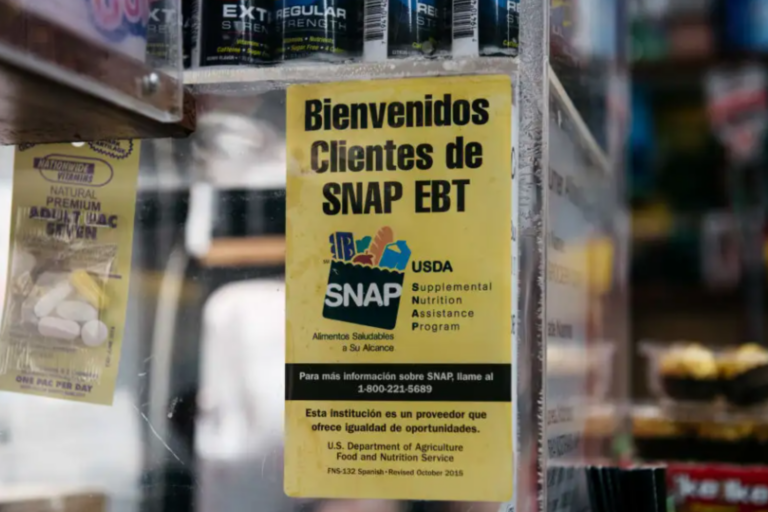

New York State covers Jaciel’s healthcare costs because he’s an American citizen. But his parents are undocumented immigrants from Mexico, who have asked us not to use the full names of anyone in the family.

To allay their constant fear of being deported at any time, Jaciel’s family is working with Neighbors Link Community Law Service in Westchester to apply for what’s called deferred action. Neighbors Link attorney Elizabeth Mastropolo said it’s granted by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) when an undocumented immigrant or their child needs life-saving medical care, and Laura fits the bill.

“She’s constantly caring for her child dealing with emergency after emergency going to the hospital,” she said. “So this is one less thing that she and her family would need to worry about, is being separated from her child.”

Only about a thousand undocumented immigrants apply for this temporary shield from deportation each year, nationally. But Jaciel’s parents almost lost out on the opportunity.

In early August, USCIS suddenly stopped taking applications — just as Jaciel’s parents were getting ready to fill out their paperwork. Applicants began getting rejection letters telling them they’d be deported in a month. There was no explanation from the Trump Administration. But a memo obtained by Politico suggested officials feared the deferrals were open to abuse.

After tremendous outcry from the public, the Trump Administration first allowed applications submitted before early August to be considered. Members of Congress called on USCIS to restore the program completely and civil rights groups in Boston filed a lawsuit. Last week, the administration reversed course altogether and said USCIS would accept new applications, too, restoring the status quo.

A USCIS spokesperson did not respond to our request for an explanation about the reversal.

For Laura, that reversal was a big relief because she and her husband can now apply. He works as a gardener and part-time at night in a laundromat so Laura can deal with their son’s medical needs and also care for their four-year-old daughter. Laura said they could never leave Jaciel alone in the U.S. if they were deported, nor could they take him to Mexico because the doctors who have been treating him since birth are here in New York.

“It was hard enough that we had to be in this fight for his life,” she explained. “Fighting with medicine and the doctors and on top of that we had to be in this legal battle,” she said, referring to the dispute over deferred action.

By restoring the shield of deportation, she said she felt like the government had recognized the humanity of immigrants.

But there’s a catch. Deferred action isn’t a formal program with set criteria for who wins and loses. It’s a form of prosecutorial discretion granted on a case-by-case basis. And it doesn’t mean the immigrant is permanently safe from deportation, just that he or she is a low priority. It’s also temporary for two years at a time. This is why immigration lawyers are cautiously optimistic.

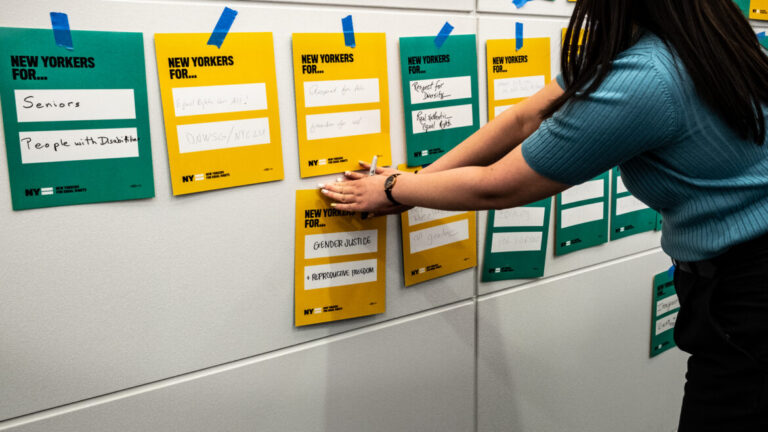

“We are remaining on guard and we will be closely monitoring how USCIS process deferred actions from this point on to make sure that the administration keeps to its word,” said Randye Retkin, director of LegalHealth at New York Legal Assistance Group.

Her organization files more applications than anyone else in the metro region, about 25 each year after carefully vetting for medically-needy individuals. Some want to stay for cancer treatments and others are caring for very sick children. LegalHealth has learned which cases are most likely to win based on a track record. But Retkin said it’s not clear if USCIS will continue granting deferred action the way it did before the uproar in August.

Nonetheless, she viewed the reversal as a big win, calling it the “direct result of an incredible organized advocacy effort on a national scale.

“And it is a wonderful victory for immigrants and their families dealing with serious illness.”

Andres O’Hare and Lidia Tapia-Hernández contributed translation for this article.

Article originally published in Gothamist on September 25, 2019.