Mikal Weiner

Prism

Brooklyn, New York, real estate is a hot commodity. Prices have risen by leaps and bounds, with the median sales price setting “a new record for the seventh time in the past eight quarters” and nearly half of all properties (43.5%) selling for over $1 million. For residents of central Brooklyn, neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant (Bed-Stuy), Crown Heights, East New York, and nearby areas, not only are they at risk from the effects of gentrification, their homes have also become very attractive targets for housing thieves.

Deed theft has been a major contributor to the displacement of mostly Black and brown homeowners, many of whom had owned properties for decades. This displacement has resulted in a rapid demographic shift in the area. According to the NYU Furman Center, only 45.6% of Bed-Stuy’s population identified as Black in 2015-19, a drastic drop from 2000 census data that shows the same population at 74.9%. The effects of area real estate development are equally staggering. Only 94 new units were certified for occupancy in Bed-Stuy in 2000; in 2020, that number was 850. Construction is underway everywhere, as industrious teams turn single-family brownstones into multi-unit studios and one-bedrooms to lease to young, mostly non-Black, short-term renters.

“Gentrifying neighborhoods are most vulnerable to real estate scams, especially where the neighborhoods have seen dramatic changes, particularly with race and income demographics,” said Noelle Eberts, supervising attorney of consumer protection at New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG).

After years of neglect by the city, the area has suddenly become a gold mine, one that arguably is more likely to put homeowners at risk than benefit them. And residents—particularly Black and brown families—are being left to fend for themselves as they become prime targets for devastating scams that can steal homes and their value, leaving families bankrupt, deeply in debt, unhoused, or worse.

Losing a home in Bed-Stuy

Bedford-Stuyvesant is home to one of the first free Black communities in the U.S., a community originally known as Weeksville when it was founded in the mid-1800s. The area remained predominantly Black until the early aughts; due to the practice of “redlining” this was one of the only areas where the Black population in New York could buy property.

Sherlivia Thomas-Murchison was raised in Bed-Stuy public housing before her mother, Margaret Blow, and their neighbors were able to purchase the city-owned property they lived in through the TIL (Tenant Interim Lease) program. At the time, the building was infested by rats and cockroaches and had to be overhauled.

“The roaches would get into our food in the cabinets—we would have to shake roaches out of our cereal first,” Thomas-Murchison said.

Blow and her collaborators formed a cooperative to buy a building on Madison Street in 1991 and refurbished it. In fact, despite being only 19 years old at the time, Thomas-Murchison herself purchased one of the apartments in the building for $2,000. She did this at her mother’s urging—Blow wanted to ensure her children would be financially secure.

But in 2018, Thomas-Murchison’s family home was one of about 700 properties seized by New York City’s department of Housing Preservation & Development (HPD) as a part of the controversial Third Party Transfer (TPT) program, through which city officials can declare an owner unfit to care for their asset and reassign that asset to a third party. The program ostensibly only seizes properties if they show “significant delinquent municipal charges and poor housing conditions,” but buildings have been seized for myriad perplexing reasons, including the proliferation of deed and equity frauds in Central Brooklyn. But residents like Thomas-Murchison have stated that the program seizes housing in ways that mimic deed theft with the official stamp of the city. For property to be seized through TPT, the action must be approved by city council members who, according to Councilmember Robert Cornegy, lack the time and resources to inspect the homes in question. At a 2019 city council meeting, Cornegy was adamant that HPD staff had misled the council members as to the state of the properties. “Did every council member go to every third party transfer on the list in their district and visit them?” said Cornegy, “No […] I did visit a couple, but there were so many on my list that it wasn’t even humanly possible even in that period to visit them.”

Thomas-Murchison is currently part of a class-action lawsuit against the city that will be heading to trial.

How to steal a house

According to Eva Velasquez, president and CEO of the ID Theft Resource Center, the system for registering property ownership in the U.S. is “fractured.” She describes a convoluted framework that changes from county to county, creating confusion among homeowners—especially those who may not be comfortable with checking on their property registration online or have access to a computer and internet connection with which to do so. As a result, the system can be vulnerable to forgery, particularly if the home in question isn’t occupied, as in the case of a second home or an inherited property.

Scammers will forge a new deed and file it with the County Clerk’s office, changing the ownership of someone’s property without their knowledge. Forgers can falsify notarization for property registration that overworked assessor’s office clerks might miss, notarize documents themselves, or work with notaries in on the scheme. Further, a notary public needs only to notarize a document after it has been signed and can be lax in checking someone’s identification. Once a document gets notarized, it will be filed with the County Clerk, no questions asked, and the house will belong to the scammer.

While forgeries are often clear-cut criminal cases, Toby Cohen, a real estate attorney with extensive experience in deed fraud, says that it’s harder to prevent scammers from making false promises to desperate homeowners and using shell corporations to move properties around. Both deed theft—stealing someone’s home—and equity theft—stealing the value of someone’s home, sometimes while they’re still living in it, can be some of the hardest crimes to prosecute in the courts, often due to perpetrators’ use of shell corporation structures to distance themselves from the theft.

“[Deed theft by con artists] tends to happen more in communities of color,” Gloria Sandiford, president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Real Estate Council, who was born and raised in Bed-Stuy said. “I’ve seen more stories than I care to go into, all very disturbing.”

For instance, a con artist can mislead a homeowner into signing away their rights without disclosing what it is they’re signing or pressure someone with money troubles to sign away a property with the promise of repaying debts. The problem is that this type of crime rests in a gray area between civil and criminal because homeowners do sign documents, even under false pretenses, and are of sound mind when they do so, Velasquez says. It’s also difficult to prove because it requires giving evidence of intent when “it’s almost impossible to try to get inside someone else’s head.” If a bad actor convinces someone to transfer their deed and then quickly takes out a mortgage on the property or transfers it to a second entity—such as a bank that issues a mortgage to the scammer—the home is lost forever.

“Under the law, the second company is called a bona fide purchaser, meaning they weren’t part of the original fraud and had no reason to know there was a fraud,” Cohen said. “They’re protected under the law, and I cannot get the property back from them.”

What happens next is ugly: scammers can evict rightful homeowners because they don’t own the house anymore, or they may take out an extensive mortgage on the property—one that homeowners won’t find out about until their property is being foreclosed on. This is how many homeowners end up unhoused, trying to figure out what just happened to them and where they can go next. By that time, the thieves are either long gone or hiding behind the veil of an anonymous LLC.

The onus then falls upon the victim to prove the new deed is, in fact, a fake. This comes with legal fees, not to mention time, effort, loss of income (if the original owner was collecting rent), and the trauma of being uprooted from one’s home. Thomas-Murchison, for example, spent two years living in her car with her children after being forcibly evicted from her home. Sandiford recalls one woman who spent years living in an illegal basement with no heat after losing the home she’d inherited to scammers. Even though the woman eventually got the home back, she was so behind on the mortgage, and her health had become so bad that she was still forced to sell and move into a nursing home, where she eventually passed away.

“You see homeless people out here [and] you wonder what happened to them,” Sandiford said. “You’ll be surprised how many of these stories are their story.”

The impact of COVID-19

The global pandemic upended every industry, but the real estate sector saw a particularly drastic impact. The Federal Reserve responded to the standstill economy by lowering interest rates, and prospective buyers jumped at the opportunity to take out mortgages at low rates. With demand skyrocketing, home prices soared. Meanwhile, job loss disproportionately impacted people with lower incomes, and many homeowners in less affluent areas found themselves struggling to keep up with payments.

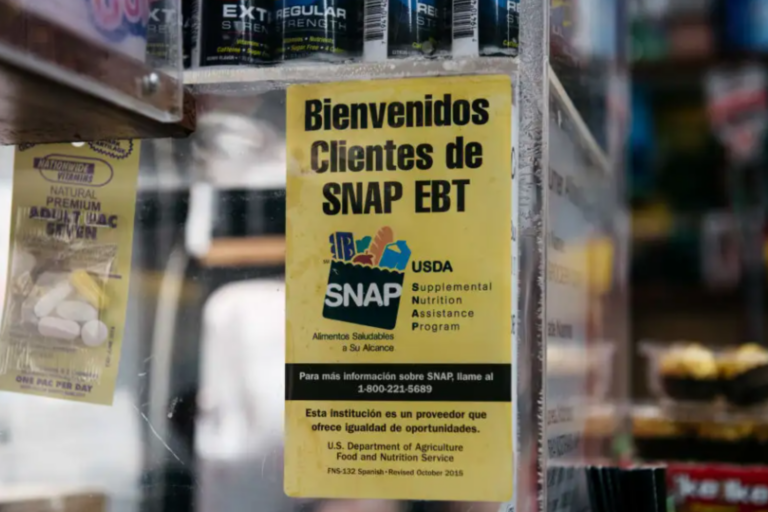

In New York City, the Department of Financial Services attempted to aid homeowners who were falling behind on payments, mostly through the CARES Act. Unfortunately, applying for aid was not a straightforward, user-friendly process. Plus, some homeowners—who often fall into vulnerable groups that are targeted by scammers—may not have known about these relief programs or had access to the necessary technology and know-how for applying. According to Kevin Wolfe, senior government affairs manager at the Center for NYC Neighborhoods (CNYCN), seniors living on a fixed income but who have equity in their homes became targets for fraudsters, especially if they weren’t aware that a property they bought for a song 50 years ago was now worth millions of dollars. All this created chaos in the realm of real estate.

“This is a terribly lucrative type of crime because we’re talking about high-dollar-value items that are so in demand,” Velasquez said. “In my expert opinion, there’s no way [property theft] has not increased over the last couple of years.”

Preventive efforts

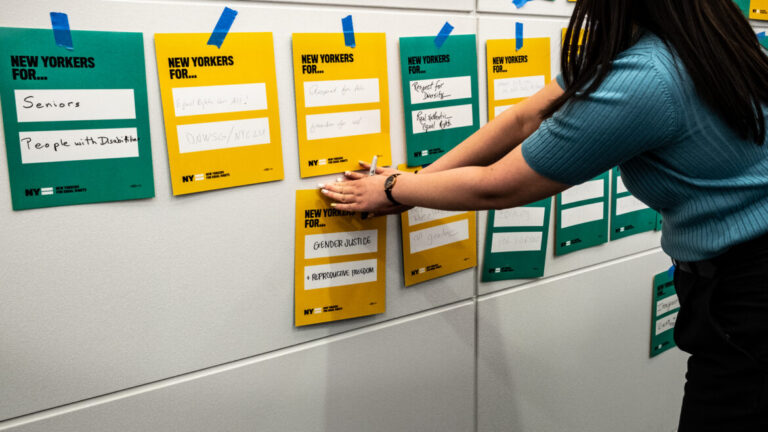

In January of 2020, New York Attorney General Letitia James released a statement saying “New York City received around 3,000 complaints about deed theft between 2014-19, 45% of which came from Brooklyn.” The Office of the Attorney General (OAG) has made deed fraud a focal point of its operations, and recently awarded a grant of $800,000 to HPD and CNYCN in an attempt to “increas[e] awareness of scams and deed theft in vulnerable neighborhoods.” According to Wolfe, CNYCN’s Protect Our Homes campaign has reached 30,000 New Yorkers since the onset of the global pandemic. Despite this success, he emphasizes the need for increased homeowner protections and outreach.

Bed-Stuy residents are frustrated that while property theft is common knowledge, the efforts they’ve seen to combat it are lacking. Dar Lawrence, who was born and raised in Bed-Stuy’s Stuyvesant Heights, calls it “shameful” and says it’s common enough for most people to know a neighbor, friend, or community member who has been victimized. Additional residents interviewed for this piece expressed a similar sense of frustration.

“Where is the outreach and information from churches, local politicians, community activists, libraries?” said Lawrence. “This may be happening in clusters, but not consistently and repeatedly. Inevitably, folks will slip through the cracks.”

There are public and private sector initiatives to push back against deed and equity theft, but they’ve had inconsistent results. The New York State Senate introduced Senate Bill S5756A, which would require notaries public or commissioners of deeds to be more stringent in their verification before affixing a seal to a document that transfers ownership of a deed, and Senate Bill S6171, which would provide additional time and information before homeowners decide to transfer ownership of their home and remove existing hurdles that plaintiffs currently face. However, both bills have languished in committees since their introduction to the State Senate during the 2017-18 legislative session.

While governmental offices like the New York City Register have put alert services into effect, notifying homeowners if a document has been filed against their property, homeowners have to know the service exists and sign up to receive notifications. Additionally, some advocates feel that realtors and other professionals in the property industry bear some responsibility for protecting homeowners.

“An effective and reputable real estate professional will never agree to be an instrument for completing a crime,” said Kris Lippi, real estate broker and CEO of ISoldMyHouse.com. “As part of the due diligence, agents, brokers, and realtors must verify the deed and title with the registry and look at the history of transfers to identify red flags or abrupt transfers.”

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) declined to comment for this piece.

Meanwhile, organizations like NYLAG work with homeowners in all five boroughs and on Long Island to provide accurate information and resources about homeowner rights. According to Eberts, they also try to help homeowners resolve mortgage issues before they can fall prey to scammers and keep an eye out to identify new scammers and types of scams.

Other avenues available to those who fear they may have been victimized include the Homeowner Protection Program (HOPP), a network launched and championed by Attorney General James, as well as Protect Our Homes, in which local organizations in Central Brooklyn, Southeast Queens, and North Bronx cooperatively combat the displacement of local communities due gentrification and fraud. Homeowners facing fraud or the threat of foreclosure can also receive legal aid and advice from the legal team at CNYCN.

Terzero (patent pending), is another initiative intended to discourage scammers by sticking the scammer with what Cohen calls a “hot potato deed that can’t be sold.” Deeds registered with Terzero would be locked into a person’s name so they cannot be resold to a bona fide purchaser, even if a thief forges a new deed and files it with the city clerk. However, at $499, the service is less accessible to homeowners with limited financial resources, although the company claims to be working to make it available to homeowners of all backgrounds and economic levels.

Buying a home is a major milestone. Buy a house, common wisdom says, and that purchase will lead to stability, upward mobility, and generational wealth. But houses aren’t just investments—they’re homes, ones that homeowners hope to pass down to successive generations.

“For many homeowners there is no monetary value that can compensate them for the loss of their family home,” Eberts said. “Their home is a piece of their identity—where they grew up, where they raised their children, and it has been passed down through generations—you can’t put a price tag on it.”

Originally published in Prism on August 8, 2022