By Virginia Breen

The City

Retired FDNY firefighter Bryan Horan got through 9/11, a heart attack and lung problems, while his wife, Moira, beat breast cancer — all without ever getting around to writing a will.

The coronavirus pandemic made the couple finally start the paperwork.

“Seeing all the death on the news with this thing, we just looked at each other and said, ‘We gotta get our acts together and do something,’” said Bryan Horan, 65.

The Horans filled out the paperwork last week and mailed in a draft to Barasch & McGarry, a Manhattan law firm that has been offering complimentary wills to firefighters for nearly two decades.

“So now it’s done and I don’t have to deal with it,” said Bryan Horan, a transplanted Brooklynite now living in Spring Lake, N.J. “Because really, nobody wants to deal with it.”

Moira Horan, 64, a retired office worker, added, “The paperwork literally sat in our living room 99% done for the longest time. But now that we finished it and mailed it, I feel a sense of relief. It’s morbid to think about, but it’s great to be done.”

The Horans are among the families confronting their own mortality amid the coronavirus pandemic and finally starting end-of-life planning.

While some New York City lawyers report an uptick in will-writing and other advance-planning inquiries, others note a decline among those who may need it most amid the pandemic: the elderly and infirm, especially as coronavirus ravages nursing homes.

‘Ringing off the Hook’

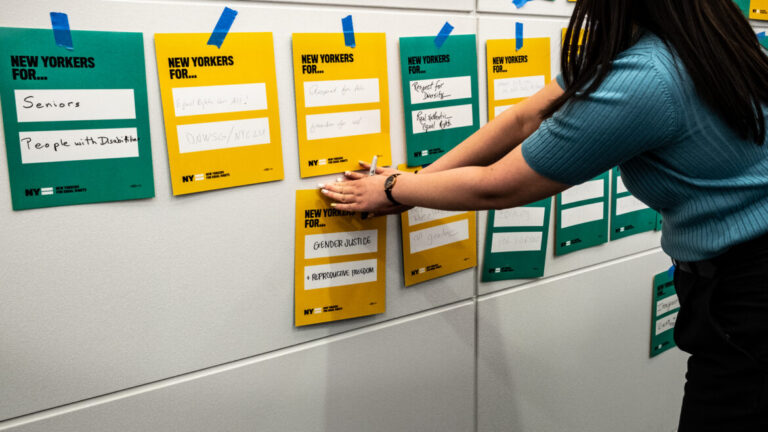

The New York Legal Assistance Group, a not-for-profit law office that provides free civil legal services to low-income New Yorkers, reported a slight downturn in end-of-life planning inquiries since the pandemic began. In February, the group had 92 requests for advance-planning and elder-law assistance from 31 senior centers and nursing homes.

Last month, the nonprofit saw “slightly less,” said Maria Hunter, director of the public benefits unit.

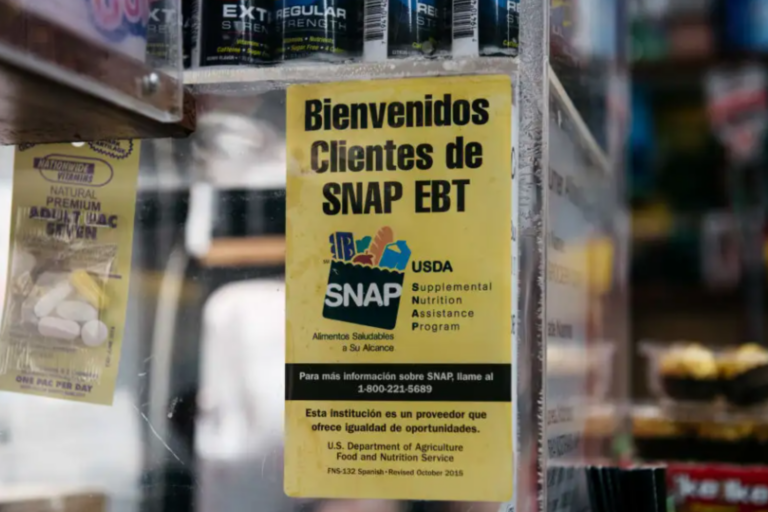

“Right now, the social workers and caseworkers who normally do referrals are focusing on urgent needs like ensuring seniors have access to food and are following safety protocols,” Hunter told THE CITY. “We anticipate that there will be an increase once food access and other vital needs that are difficult to meet while isolated are addressed for our clients. I’m guessing things will pick up.”

Others in the city and elsewhere, however, are writing wills in greater numbers, either in consultation with attorneys or via free or low-cost digital legal-services companies.

“We’ve seen a huge uptick – a 427% increase — in planning engagement, and we serve more than half a million people each month,” said Suelin Chen, CEO of the Boston-based startup Cake, an end-of-life planning platform.

Cake offers customers free will writing and other advance-planning forms, and makes money by offering a digital marketplace with links to third-party insurance and legal-services companies.

Traditional law offices report similar spikes in advance-directive queries.

“I’ve been blown away by the increase in requests,” said Michael Barasch, a partner at Barasch & McGarry. The firm has already completed more than 4,000 free wills and healthcare proxies for active and retired city firefighters and their spouses since the terror attacks in 2001.

“The phones are ringing off the hook,” Barasch said, noting he had to dedicate an additional paralegal to handle will requests. “I’d say we’ve seen a 50% increase, hundreds more in the last three and a half weeks.”

Psychological Blocks

Barasch noted that before the coronavirus pandemic, first responders had traditionally avoided writing wills, despite the risks of their job and the firm’s offer. He recalled asking an FDNY psychologist to explain the hesitancy.

“She said to think of it this way: If you’re so confident in your equipment and your training and in the guys you work with that you can run into a fire, you have to believe everything’s going to be fine,” he said. “That confidence works against them in this case.”

Barasch cited squabbles among surviving family members of 9/11 victims as evidence of the need for people to make their estate wishes known. “Bottom line: Everyone should have a will,” he said.

Hunter agreed, and noted that the New York Legal Assistance Group’s Legal Resource Hotline and Coronavirus Legal Planning Page offer guidance on such issues as will writing and health care directives during the pandemic.

“As gruesome as it sounds, right now everyone should be thinking about what level of medical care or intervention they would want” should they become incapacitated by COVID-19, Hunter said.

“The older and more vulnerable you are, the more important it becomes to let your loved ones know what your wishes are.”

Getting a Proxy

Part of that advanced planning involves completing a health care proxy, a legal document that lets a person name someone else to make decisions about their medical care, including decisions about life-sustaining treatment, if they cannot speak for themselves.

A second document, a living will, allows a person to spell out their wishes about medical care in the event they are unable to make their own medical decisions. The living will takes effect if a person becomes terminally ill, unconscious or minimally conscious due to brain damage.

A power of attorney document allows a patient to share control of their finances and property with someone, called an “agent.” An agent is legally required to follow the directions of the patient, or to act in their best interest.

Hunter pointed out that the pandemic has transformed end-of-life planning in a number of ways. Social distancing has made it harder for some people to complete documents with proper witnessing or notarization. The state has loosened some requirements in light of the pandemic.

Notaries, for example, are now allowed to use audio-video technology. According to a March executive order from Gov. Andrew Cuomo, “Any notarial act that is required under New York State law is authorized to be performed utilizing audio-video technology” that allows for direct interaction between the client and the notary.

Pre-recorded videos of the person signing are not allowed. The client must also present valid photo identification and be physically present in New York State.

Don’t ‘Freak Out’

Hunter noted that “people shouldn’t really freak out” if they have not yet completed advanced-planning documents, as they’re called.

New York’s 2010 Family Health Care Decisions Act allows a patient’s family member or close friend to make health care choices in a hospital or nursing home for someone who lacks “decisional capacity” and hasn’t signed a health-care proxy.

The determination of incapacity is made by the attending physician. In a nursing home or communal-living arrangement, a social worker must confirm the primary decision. If there is a disagreement, the facility’s ethics review committee makes the final call.

Still, given the current state of overcrowded and understaffed city hospitals and nursing homes, in which patients may be cut off from their advocate due to no-visitor policies, experts recommend having a digital or physical copy of advanced-planning documents.

While lawyers recommend having a written will, if a person dies without one — the legal term is “intestate” — their property is distributed according to state law. Who gets what depends on their relationship to the deceased.

Before coronavirus, most Americans did not bother with writing wills. A recent study published in the journal Health Affairs revealed that only one in three U.S. adults, about 37%, had completed advance directives, including 29% with living wills.

Those with chronic illnesses were only slightly more likely to have completed advanced health care directives than healthy adults (38% versus 33%), the study found.

For the Horans, the pandemic offered the push they needed to complete their end-of-life directives.

Brian Horan, a 23-year veteran of the FDNY who retired out of Engine Company 248 in East Flatbush in 2011, said that he and his wife of 37 years wanted to leave clear directives to remove some of the burden from their only daughter.

“If you avoid making the plans, it’s a way to avoid acknowledging and accepting the reality of death,” Moira Horan added. “So initially it was tough, but honestly it wasn’t as awful as I thought it would be.”

Originally published in The City on April 20, 2020.